The Fixation of Belief

Charles S. Peirce

Popular Science Monthly 12 (November 1877), 1-15.

I

Few persons care to study logic, because everybody conceives himself to be proficient enough in the art of reasoning already. But I observe that this satisfaction is limited to one's own ratiocination, and does not extend to that of other men.

We come to the full possession of our power of drawing inferences, the last of all our faculties; for it is not so much a natural gift as a long and difficult art. The history of its practice would make a grand subject for a book. The medieval schoolman, following the Romans, made logic the earliest of a boy's studies after grammar, as being very easy. So it was as they understood it. Its fundamental principle, according to them, was, that all knowledge rests either on authority or reason; but that whatever is deduced by reason depends ultimately on a premiss derived from authority. Accordingly, as soon as a boy was perfect in the syllogistic procedure, his intellectual kit of tools was held to be complete.

To Roger Bacon, that remarkable mind who in the middle of the thirteenth century was almost a scientific man, the schoolmen's conception of reasoning appeared only an obstacle to truth. He saw that experience alone teaches anything -- a proposition which to us seems easy to understand, because a distinct conception of experience has been handed down to us from former generations; which to him likewise seemed perfectly clear, because its difficulties had not yet unfolded themselves. Of all kinds of experience, the best, he thought, was interior illumination, which teaches many things about Nature which the external senses could never discover, such as the transubstantiation of bread.

Four centuries later, the more celebrated Bacon, in the first book of his Novum Organum, gave his clear account of experience as something which must be open to verification and reexamination. But, superior as Lord Bacon's conception is to earlier notions, a modern reader who is not in awe of his grandiloquence is chiefly struck by the inadequacy of his view of scientific procedure. That we have only to make some crude experiments, to draw up briefs of the results in certain blank forms, to go through these by rule, checking off everything disproved and setting down the alternatives, and that thus in a few years physical science would be finished up -- what an idea! "He wrote on science like a Lord Chancellor," indeed, as Harvey, a genuine man of science said.

The early scientists, Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, Kepler, Galileo, Harvey, and Gilbert, had methods more like those of their modern brethren. Kepler undertook to draw a curve through the places of Mars; and to state the times occupied by the planet in describing the different parts of that curve; but perhaps his greatest service to science was in impressing on men's minds that this was the thing to be done if they wished to improve astronomy; that they were not to content themselves with inquiring whether one system of epicycles was better than another but that they were to sit down to the figures and find out what the curve, in truth, was. He accomplished this by his incomparable energy and courage, blundering along in the most inconceivable way (to us), from one irrational hypothesis to another, until, after trying twenty-two of these, he fell, by the mere exhaustion of his invention, upon the orbit which a mind well furnished with the weapons of modern logic would have tried almost at the outset.

In the same way, every work of science great enough to be well remembered for a few generations affords some exemplification of the defective state of the art of reasoning of the time when it was written; and each chief step in science has been a lesson in logic. It was so when Lavoisier and his contemporaries took up the study of Chemistry. The old chemist's maxim had been, "Lege, lege, lege, labora, ora, et relege." Lavoisier's method was not to read and pray, but to dream that some long and complicated chemical process would have a certain effect, to put it into practice with dull patience, after its inevitable failure, to dream that with some modification it would have another result, and to end by publishing the last dream as a fact: his way was to carry his mind into his laboratory, and literally to make of his alembics and cucurbits instruments of thought, giving a new conception of reasoning as something which was to be done with one's eyes open, in manipulating real things instead of words and fancies.

The Darwinian controversy is, in large part, a question of logic. Mr. Darwin proposed to apply the statistical method to biology. The same thing has been done in a widely different branch of science, the theory of gases. Though unable to say what the movements of any particular molecule of gas would be on a certain hypothesis regarding the constitution of this class of bodies, Clausius and Maxwell were yet able, eight years before the publication of Darwin's immortal work, by the application of the doctrine of probabilities, to predict that in the long run such and such a proportion of the molecules would, under given circumstances, acquire such and such velocities; that there would take place, every second, such and such a relative number of collisions, etc.; and from these propositions were able to deduce certain properties of gases, especially in regard to their heat-relations. In like manner, Darwin, while unable to say what the operation of variation and natural selection in any individual case will be, demonstrates that in the long run they will, or would, adapt animals to their circumstances. Whether or not existing animal forms are due to such action, or what position the theory ought to take, forms the subject of a discussion in which questions of fact and questions of logic are curiously interlaced.

II

The object of reasoning is to find out, from the consideration of what we already know, something else which we do not know. Consequently, reasoning is good if it be such as to give a true conclusion from true premisses, and not otherwise. Thus, the question of validity is purely one of fact and not of thinking. A being the facts stated in the premisses and B being that concluded, the question is, whether these facts are really so related that if A were B would generally be. If so, the inference is valid; if not, not. It is not in the least the question whether, when the premisses are accepted by the mind, we feel an impulse to accept the conclusion also. It is true that we do generally reason correctly by nature. But that is an accident; the true conclusion would remain true if we had no impulse to accept it; and the false one would remain false, though we could not resist the tendency to believe in it.

We are, doubtless, in the main logical animals, but we are not perfectly so. Most of us, for example, are naturally more sanguine and hopeful than logic would justify. We seem to be so constituted that in the absence of any facts to go upon we are happy and self-satisfied; so that the effect of experience is continually to contract our hopes and aspirations. Yet a lifetime of the application of this corrective does not usually eradicate our sanguine disposition. Where hope is unchecked by any experience, it is likely that our optimism is extravagant. Logicality in regard to practical matters (if this be understood, not in the old sense, but as consisting in a wise union of security with fruitfulness of reasoning) is the most useful quality an animal can possess, and might, therefore, result from the action of natural selection; but outside of these it is probably of more advantage to the animal to have his mind filled with pleasing and encouraging visions, independently of their truth; and thus, upon unpractical subjects, natural selection might occasion a fallacious tendency of thought.

That which determines us, from given premisses, to draw one inference rather than another, is some habit of mind, whether it be constitutional or acquired. The habit is good or otherwise, according as it produces true conclusions from true premisses or not; and an inference is regarded as valid or not, without reference to the truth or falsity of its conclusion specially, but according as the habit which determines it is such as to produce true conclusions in general or not. The particular habit of mind which governs this or that inference may be formulated in a proposition whose truth depends on the validity of the inferences which the habit determines; and such a formula is called a guiding principle of inference. Suppose, for example, that we observe that a rotating disk of copper quickly comes to rest when placed between the poles of a magnet, and we infer that this will happen with every disk of copper. The guiding principle is, that what is true of one piece of copper is true of another. Such a guiding principle with regard to copper would be much safer than with regard to many other substances -- brass, for example.

A book might be written to signalize all the most important of these guiding principles of reasoning. It would probably be, we must confess, of no service to a person whose thought is directed wholly to practical subjects, and whose activity moves along thoroughly-beaten paths. The problems that present themselves to such a mind are matters of routine which he has learned once for all to handle in learning his business. But let a man venture into an unfamiliar field, or where his results are not continually checked by experience, and all history shows that the most masculine intellect will ofttimes lose his orientation and waste his efforts in directions which bring him no nearer to his goal, or even carry him entirely astray. He is like a ship in the open sea, with no one on board who understands the rules of navigation. And in such a case some general study of the guiding principles of reasoning would be sure to be found useful.

The subject could hardly be treated, however, without being first limited; since almost any fact may serve as a guiding principle. But it so happens that there exists a division among facts, such that in one class are all those which are absolutely essential as guiding principles, while in the others are all which have any other interest as objects of research. This division is between those which are necessarily taken for granted in asking why a certain conclusion is thought to follow from certain premisses, and those which are not implied in such a question. A moment's thought will show that a variety of facts are already assumed when the logical question is first asked. It is implied, for instance, that there are such states of mind as doubt and belief -- that a passage from one to the other is possible, the object of thought remaining the same, and that this transition is subject to some rules by which all minds are alike bound. As these are facts which we must already know before we can have any clear conception of reasoning at all, it cannot be supposed to be any longer of much interest to inquire into their truth or falsity. On the other hand, it is easy to believe that those rules of reasoning which are deduced from the very idea of the process are the ones which are the most essential; and, indeed, that so long as it conforms to these it will, at least, not lead to false conclusions from true premisses. In point of fact, the importance of what may be deduced from the assumptions involved in the logical question turns out to be greater than might be supposed, and this for reasons which it is difficult to exhibit at the outset. The only one which I shall here mention is, that conceptions which are really products of logical reflection, without being readily seen to be so, mingle with our ordinary thoughts, and are frequently the causes of great confusion. This is the case, for example, with the conception of quality. A quality, as such, is never an object of observation. We can see that a thing is blue or green, but the quality of being blue and the quality of being green are not things which we see; they are products of logical reflections. The truth is, that common-sense, or thought as it first emerges above the level of the narrowly practical, is deeply imbued with that bad logical quality to which the epithet metaphysical is commonly applied; and nothing can clear it up but a severe course of logic.

III

We generally know when we wish to ask a question and when we wish to pronounce a judgment, for there is a dissimilarity between the sensation of doubting and that of believing.

But this is not all which distinguishes doubt from belief. There is a practical difference. Our beliefs guide our desires and shape our actions. The Assassins, or followers of the Old Man of the Mountain, used to rush into death at his least command, because they believed that obedience to him would insure everlasting felicity. Had they doubted this, they would not have acted as they did. So it is with every belief, according to its degree. The feeling of believing is a more or less sure indication of there being established in our nature some habit which will determine our actions. Doubt never has such an effect.

Nor must we overlook a third point of difference. Doubt is an uneasy and dissatisfied state from which we struggle to free ourselves and pass into the state of belief; while the latter is a calm and satisfactory state which we do not wish to avoid, or to change to a belief in anything else. On the contrary, we cling tenaciously, not merely to believing, but to believing just what we do believe.

Thus, both doubt and belief have positive effects upon us, though very different ones. Belief does not make us act at once, but puts us into such a condition that we shall behave in some certain way, when the occasion arises. Doubt has not the least such active effect, but stimulates us to inquiry until it is destroyed. This reminds us of the irritation of a nerve and the reflex action produced thereby; while for the analogue of belief, in the nervous system, we must look to what are called nervous associations -- for example, to that habit of the nerves in consequence of which the smell of a peach will make the mouth water.

IV

The irritation of doubt causes a struggle to attain a state of belief. I shall term this struggle inquiry, though it must be admitted that this is sometimes not a very apt designation.

The irritation of doubt is the only immediate motive for the struggle to attain belief. It is certainly best for us that our beliefs should be such as may truly guide our actions so as to satisfy our desires; and this reflection will make us reject every belief which does not seem to have been so formed as to insure this result. But it will only do so by creating a doubt in the place of that belief. With the doubt, therefore, the struggle begins, and with the cessation of doubt it ends. Hence, the sole object of inquiry is the settlement of opinion. We may fancy that this is not enough for us, and that we seek, not merely an opinion, but a true opinion. But put this fancy to the test, and it proves groundless; for as soon as a firm belief is reached we are entirely satisfied, whether the belief be true or false. And it is clear that nothing out of the sphere of our knowledge can be our object, for nothing which does not affect the mind can be the motive for mental effort. The most that can be maintained is, that we seek for a belief that we shall think to be true. But we think each one of our beliefs to be true, and, indeed, it is mere tautology to say so.

That the settlement of opinion is the sole end of inquiry is a very important proposition. It sweeps away, at once, various vague and erroneous conceptions of proof. A few of these may be noticed here.

1. Some philosophers have imagined that to start an inquiry it was only necessary to utter a question whether orally or by setting it down upon paper, and have even recommended us to begin our studies with questioning everything! But the mere putting of a proposition into the interrogative form does not stimulate the mind to any struggle after belief. There must be a real and living doubt, and without this all discussion is idle.

2. It is a very common idea that a demonstration must rest on some ultimate and absolutely indubitable propositions. These, according to one school, are first principles of a general nature; according to another, are first sensations. But, in point of fact, an inquiry, to have that completely satisfactory result called demonstration, has only to start with propositions perfectly free from all actual doubt. If the premisses are not in fact doubted at all, they cannot be more satisfactory than they are.

3. Some people seem to love to argue a point after all the world is fully convinced of it. But no further advance can be made. When doubt ceases, mental action on the subject comes to an end; and, if it did go on, it would be without a purpose.

V

If the settlement of opinion is the sole object of inquiry, and if belief is of the nature of a habit, why should we not attain the desired end, by taking as answer to a question any we may fancy, and constantly reiterating it to ourselves, dwelling on all which may conduce to that belief, and learning to turn with contempt and hatred from anything that might disturb it? This simple and direct method is really pursued by many men. I remember once being entreated not to read a certain newspaper lest it might change my opinion upon free-trade. "Lest I might be entrapped by its fallacies and misstatements," was the form of expression. "You are not," my friend said, "a special student of political economy. You might, therefore, easily be deceived by fallacious arguments upon the subject. You might, then, if you read this paper, be led to believe in protection. But you admit that free-trade is the true doctrine; and you do not wish to believe what is not true." I have often known this system to be deliberately adopted. Still oftener, the instinctive dislike of an undecided state of mind, exaggerated into a vague dread of doubt, makes men cling spasmodically to the views they already take. The man feels that, if he only holds to his belief without wavering, it will be entirely satisfactory. Nor can it be denied that a steady and immovable faith yields great peace of mind. It may, indeed, give rise to inconveniences, as if a man should resolutely continue to believe that fire would not burn him, or that he would be eternally damned if he received his ingesta otherwise than through a stomach-pump. But then the man who adopts this method will not allow that its inconveniences are greater than its advantages. He will say, "I hold steadfastly to the truth, and the truth is always wholesome." And in many cases it may very well be that the pleasure he derives from his calm faith overbalances any inconveniences resulting from its deceptive character. Thus, if it be true that death is annihilation, then the man who believes that he will certainly go straight to heaven when he dies, provided he have fulfilled certain simple observances in this life, has a cheap pleasure which will not be followed by the least disappointment. A similar consideration seems to have weight with many persons in religious topics, for we frequently hear it said, "Oh, I could not believe so-and-so, because I should be wretched if I did." When an ostrich buries its head in the sand as danger approaches, it very likely takes the happiest course. It hides the danger, and then calmly says there is no danger; and, if it feels perfectly sure there is none, why should it raise its head to see? A man may go through life, systematically keeping out of view all that might cause a change in his opinions, and if he only succeeds -- basing his method, as he does, on two fundamental psychological laws -- I do not see what can be said against his doing so. It would be an egotistical impertinence to object that his procedure is irrational, for that only amounts to saying that his method of settling belief is not ours. He does not propose to himself to be rational, and, indeed, will often talk with scorn of man's weak and illusive reason. So let him think as he pleases.

But this method of fixing belief, which may be called the method of tenacity, will be unable to hold its ground in practice. The social impulse is against it. The man who adopts it will find that other men think differently from him, and it will be apt to occur to him, in some saner moment, that their opinions are quite as good as his own, and this will shake his confidence in his belief. This conception, that another man's thought or sentiment may be equivalent to one's own, is a distinctly new step, and a highly important one. It arises from an impulse too strong in man to be suppressed, without danger of destroying the human species. Unless we make ourselves hermits, we shall necessarily influence each other's opinions; so that the problem becomes how to fix belief, not in the individual merely, but in the community.

Let the will of the state act, then, instead of that of the individual. Let an institution be created which shall have for its object to keep correct doctrines before the attention of the people, to reiterate them perpetually, and to teach them to the young; having at the same time power to prevent contrary doctrines from being taught, advocated, or expressed. Let all possible causes of a change of mind be removed from men's apprehensions. Let them be kept ignorant, lest they should learn of some reason to think otherwise than they do. Let their passions be enlisted, so that they may regard private and unusual opinions with hatred and horror. Then, let all men who reject the established belief be terrified into silence. Let the people turn out and tar-and-feather such men, or let inquisitions be made into the manner of thinking of suspected persons, and when they are found guilty of forbidden beliefs, let them be subjected to some signal punishment. When complete agreement could not otherwise be reached, a general massacre of all who have not thought in a certain way has proved a very effective means of settling opinion in a country. If the power to do this be wanting, let a list of opinions be drawn up, to which no man of the least independence of thought can assent, and let the faithful be required to accept all these propositions, in order to segregate them as radically as possible from the influence of the rest of the world.

This method has, from the earliest times, been one of the chief means of upholding correct theological and political doctrines, and of preserving their universal or catholic character. In Rome, especially, it has been practised from the days of Numa Pompilius to those of Pius Nonus. This is the most perfect example in history; but wherever there is a priesthood -- and no religion has been without one -- this method has been more or less made use of. Wherever there is an aristocracy, or a guild, or any association of a class of men whose interests depend, or are supposed to depend, on certain propositions, there will be inevitably found some traces of this natural product of social feeling. Cruelties always accompany this system; and when it is consistently carried out, they become atrocities of the most horrible kind in the eyes of any rational man. Nor should this occasion surprise, for the officer of a society does not feel justified in surrendering the interests of that society for the sake of mercy, as he might his own private interests. It is natural, therefore, that sympathy and fellowship should thus produce a most ruthless power.

In judging this method of fixing belief, which may be called the method of authority, we must, in the first place, allow its immeasurable mental and moral superiority to the method of tenacity. Its success is proportionately greater; and, in fact, it has over and over again worked the most majestic results. The mere structures of stone which it has caused to be put together -- in Siam, for example, in Egypt, and in Europe -- have many of them a sublimity hardly more than rivaled by the greatest works of Nature. And, except the geological epochs, there are no periods of time so vast as those which are measured by some of these organized faiths. If we scrutinize the matter closely, we shall find that there has not been one of their creeds which has remained always the same; yet the change is so slow as to be imperceptible during one person's life, so that individual belief remains sensibly fixed. For the mass of mankind, then, there is perhaps no better method than this. If it is their highest impulse to be intellectual slaves, then slaves they ought to remain.

But no institution can undertake to regulate opinions upon every subject. Only the most important ones can be attended to, and on the rest men's minds must be left to the action of natural causes. This imperfection will be no source of weakness so long as men are in such a state of culture that one opinion does not influence another -- that is, so long as they cannot put two and two together. But in the most priest-ridden states some individuals will be found who are raised above that condition. These men possess a wider sort of social feeling; they see that men in other countries and in other ages have held to very different doctrines from those which they themselves have been brought up to believe; and they cannot help seeing that it is the mere accident of their having been taught as they have, and of their having been surrounded with the manners and associations they have, that has caused them to believe as they do and not far differently. Nor can their candour resist the reflection that there is no reason to rate their own views at a higher value than those of other nations and other centuries; thus giving rise to doubts in their minds.

They will further perceive that such doubts as these must exist in their minds with reference to every belief which seems to be determined by the caprice either of themselves or of those who originated the popular opinions. The willful adherence to a belief, and the arbitrary forcing of it upon others, must, therefore, both be given up. A different new method of settling opinions must be adopted, that shall not only produce an impulse to believe, but shall also decide what proposition it is which is to be believed. Let the action of natural preferences be unimpeded, then, and under their influence let men, conversing together and regarding matters in different lights, gradually develop beliefs in harmony with natural causes. This method resembles that by which conceptions of art have been brought to maturity. The most perfect example of it is to be found in the history of metaphysical philosophy. Systems of this sort have not usually rested upon any observed facts, at least not in any great degree. They have been chiefly adopted because their fundamental propositions seemed "agreeable to reason." This is an apt expression; it does not mean that which agrees with experience, but that which we find ourselves inclined to believe. Plato, for example, finds it agreeable to reason that the distances of the celestial spheres from one another should be proportional to the different lengths of strings which produce harmonious chords. Many philosophers have been led to their main conclusions by considerations like this; but this is the lowest and least developed form which the method takes, for it is clear that another man might find Kepler's theory, that the celestial spheres are proportional to the inscribed and circumscribed spheres of the different regular solids, more agreeable to his reason. But the shock of opinions will soon lead men to rest on preferences of a far more universal nature. Take, for example, the doctrine that man only acts selfishly -- that is, from the consideration that acting in one way will afford him more pleasure than acting in another. This rests on no fact in the world, but it has had a wide acceptance as being the only reasonable theory.

This method is far more intellectual and respectable from the point of view of reason than either of the others which we have noticed. But its failure has been the most manifest. It makes of inquiry something similar to the development of taste; but taste, unfortunately, is always more or less a matter of fashion, and accordingly metaphysicians have never come to any fixed agreement, but the pendulum has swung backward and forward between a more material and a more spiritual philosophy, from the earliest times to the latest. And so from this, which has been called the a priori method, we are driven, in Lord Bacon's phrase, to a true induction. We have examined into this a priori method as something which promised to deliver our opinions from their accidental and capricious element. But development, while it is a process which eliminates the effect of some casual circumstances, only magnifies that of others. This method, therefore, does not differ in a very essential way from that of authority. The government may not have lifted its finger to influence my convictions; I may have been left outwardly quite free to choose, we will say, between monogamy and polygamy, and, appealing to my conscience only, I may have concluded that the latter practice is in itself licentious. But when I come to see that the chief obstacle to the spread of Christianity among a people of as high culture as the Hindoos has been a conviction of the immorality of our way of treating women, I cannot help seeing that, though governments do not interfere, sentiments in their development will be very greatly determined by accidental causes. Now, there are some people, among whom I must suppose that my reader is to be found, who, when they see that any belief of theirs is determined by any circumstance extraneous to the facts, will from that moment not merely admit in words that that belief is doubtful, but will experience a real doubt of it, so that it ceases to be a belief.

To satisfy our doubts, therefore, it is necessary that a method should be found by which our beliefs may be determined by nothing human, but by some external permanency -- by something upon which our thinking has no effect. Some mystics imagine that they have such a method in a private inspiration from on high. But that is only a form of the method of tenacity, in which the conception of truth as something public is not yet developed. Our external permanency would not be external, in our sense, if it was restricted in its influence to one individual. It must be something which affects, or might affect, every man. And, though these affections are necessarily as various as are individual conditions, yet the method must be such that the ultimate conclusion of every man shall be the same. Such is the method of science. Its fundamental hypothesis, restated in more familiar language, is this: There are Real things, whose characters are entirely independent of our opinions about them; those Reals affect our senses according to regular laws, and, though our sensations are as different as are our relations to the objects, yet, by taking advantage of the laws of perception, we can ascertain by reasoning how things really and truly are; and any man, if he have sufficient experience and he reason enough about it, will be led to the one True conclusion. The new conception here involved is that of Reality. It may be asked how I know that there are any Reals. If this hypothesis is the sole support of my method of inquiry, my method of inquiry must not be used to support my hypothesis. The reply is this: 1. If investigation cannot be regarded as proving that there are Real things, it at least does not lead to a contrary conclusion; but the method and the conception on which it is based remain ever in harmony. No doubts of the method, therefore, necessarily arise from its practice, as is the case with all the others. 2. The feeling which gives rise to any method of fixing belief is a dissatisfaction at two repugnant propositions. But here already is a vague concession that there is some one thing which a proposition should represent. Nobody, therefore, can really doubt that there are Reals, for, if he did, doubt would not be a source of dissatisfaction. The hypothesis, therefore, is one which every mind admits. So that the social impulse does not cause men to doubt it. 3. Everybody uses the scientific method about a great many things, and only ceases to use it when he does not know how to apply it. 4. Experience of the method has not led us to doubt it, but, on the contrary, scientific investigation has had the most wonderful triumphs in the way of settling opinion. These afford the explanation of my not doubting the method or the hypothesis which it supposes; and not having any doubt, nor believing that anybody else whom I could influence has, it would be the merest babble for me to say more about it. If there be anybody with a living doubt upon the subject, let him consider it.

To describe the method of scientific investigation is the object of this series of papers. At present I have only room to notice some points of contrast between it and other methods of fixing belief.

This is the only one of the four methods which presents any distinction of a right and a wrong way. If I adopt the method of tenacity, and shut myself out from all influences, whatever I think necessary to doing this, is necessary according to that method. So with the method of authority: the state may try to put down heresy by means which, from a scientific point of view, seem very ill-calculated to accomplish its purposes; but the only test on that method is what the state thinks; so that it cannot pursue the method wrongly. So with the a priori method. The very essence of it is to think as one is inclined to think. All metaphysicians will be sure to do that, however they may be inclined to judge each other to be perversely wrong. The Hegelian system recognizes every natural tendency of thought as logical, although it be certain to be abolished by counter-tendencies. Hegel thinks there is a regular system in the succession of these tendencies, in consequence of which, after drifting one way and the other for a long time, opinion will at last go right. And it is true that metaphysicians do get the right ideas at last; Hegel's system of Nature represents tolerably the science of his day; and one may be sure that whatever scientific investigation shall have put out of doubt will presently receive a priori demonstration on the part of the metaphysicians. But with the scientific method the case is different. I may start with known and observed facts to proceed to the unknown; and yet the rules which I follow in doing so may not be such as investigation would approve. The test of whether I am truly following the method is not an immediate appeal to my feelings and purposes, but, on the contrary, itself involves the application of the method. Hence it is that bad reasoning as well as good reasoning is possible; and this fact is the foundation of the practical side of logic.

It is not to be supposed that the first three methods of settling opinion present no advantage whatever over the scientific method. On the contrary, each has some peculiar convenience of its own. The a priori method is distinguished for its comfortable conclusions. It is the nature of the process to adopt whatever belief we are inclined to, and there are certain flatteries to the vanity of man which we all believe by nature, until we are awakened from our pleasing dream by rough facts. The method of authority will always govern the mass of mankind; and those who wield the various forms of organized force in the state will never be convinced that dangerous reasoning ought not to be suppressed in some way. If liberty of speech is to be untrammeled from the grosser forms of constraint, then uniformity of opinion will be secured by a moral terrorism to which the respectability of society will give its thorough approval. Following the method of authority is the path of peace. Certain non-conformities are permitted; certain others (considered unsafe) are forbidden. These are different in different countries and in different ages; but, wherever you are, let it be known that you seriously hold a tabooed belief, and you may be perfectly sure of being treated with a cruelty less brutal but more refined than hunting you like a wolf. Thus, the greatest intellectual benefactors of mankind have never dared, and dare not now, to utter the whole of their thought; and thus a shade of prima facie doubt is cast upon every proposition which is considered essential to the security of society. Singularly enough, the persecution does not all come from without; but a man torments himself and is oftentimes most distressed at finding himself believing propositions which he has been brought up to regard with aversion. The peaceful and sympathetic man will, therefore, find it hard to resist the temptation to submit his opinions to authority. But most of all I admire the method of tenacity for its strength, simplicity, and directness. Men who pursue it are distinguished for their decision of character, which becomes very easy with such a mental rule. They do not waste time in trying to make up their minds what they want, but, fastening like lightning upon whatever alternative comes first, they hold to it to the end, whatever happens, without an instant's irresolution. This is one of the splendid qualities which generally accompany brilliant, unlasting success. It is impossible not to envy the man who can dismiss reason, although we know how it must turn out at last.

Such are the advantages which the other methods of settling opinion have over scientific investigation. A man should consider well of them; and then he should consider that, after all, he wishes his opinions to coincide with the fact, and that there is no reason why the results of those three first methods should do so. To bring about this effect is the prerogative of the method of science. Upon such considerations he has to make his choice -- a choice which is far more than the adoption of any intellectual opinion, which is one of the ruling decisions of his life, to which, when once made, he is bound to adhere. The force of habit will sometimes cause a man to hold on to old beliefs, after he is in a condition to see that they have no sound basis. But reflection upon the state of the case will overcome these habits, and he ought to allow reflection its full weight. People sometimes shrink from doing this, having an idea that beliefs are wholesome which they cannot help feeling rest on nothing. But let such persons suppose an analogous though different case from their own. Let them ask themselves what they would say to a reformed Mussulman who should hesitate to give up his old notions in regard to the relations of the sexes; or to a reformed Catholic who should still shrink from reading the Bible. Would they not say that these persons ought to consider the matter fully, and clearly understand the new doctrine, and then ought to embrace it, in its entirety? But, above all, let it be considered that what is more wholesome than any particular belief is integrity of belief, and that to avoid looking into the support of any belief from a fear that it may turn out rotten is quite as immoral as it is disadvantageous. The person who confesses that there is such a thing as truth, which is distinguished from falsehood simply by this, that if acted on it should, on full consideration, carry us to the point we aim at and not astray, and then, though convinced of this, dares not know the truth and seeks to avoid it, is in a sorry state of mind indeed.

Notes

1.Not quite so, but as nearly so as can be told in a few words.

Return to text.

2.I am not speaking of secondary effects occasionally produced by the interference of other impulses.

Return to text.

AddThis

7/19/09

A Summer Camp For The Kids of Free Thinkers and Atheists

Reflections on a summer camp for the children of atheists

AS PART of a travelling Christian drama group, Don Sutterfield used to perform short plays. In one, a young man gives his girlfriend a rose and tries to persuade her to have premarital sex. The couple walk off, leaving the rose behind. Jesus picks it up and starts plucking the petals. “They love me, they love me not…”

Pious audiences loved it, says Mr Sutterfield. He and his chums would stand at the altar of a Pentecostal church, speaking in tongues, laying on hands and praying for members of the congregation to be delivered from sin, sickness and sexual perversion. Occasionally, they would attempt to drive out evil spirits. It was incredibly dramatic, says Mr Sutterfield: like the movie “The Exorcist”, only with lots of exorcists. At the time, Mr Sutterfield was “immeasurably proud” of his work. But with hindsight, he thinks it was a load of mumbo-jumbo. He is now a militant atheist. He organises secular groups at universities and, this summer, volunteered at Camp Quest, a network of summer camps for secular kids. Lexington visited one in Clarksville, Ohio.

In most ways, it is like other summer camps. Kids aged 8 to 17 share cabins in the woods. During the day, they paddle canoes, shoot arrows, go swimming and explore nature. At night, they chat beneath the stars. Like other summer camps, Camp Quest satisfies a demand that springs from America’s combination of very long holidays for children and very short ones for their parents. Unlike other camps, it is staffed entirely by humanists.

They are not pushy or preachy, but scepticism flavours nearly everything they do. Lunch comes with a five-minute talk about a famous freethinker. Campers are told that invisible unicorns inhabit the forest, and offered a prize if they can prove that the unicorns do not exist. The older kids learn something about the difficulty of proving a negative. The younger ones grow giggly at the prospect of stepping in invisible unicorn poop. There’s a prize for the tidiest cabin, too, because “cleanliness is next to godlessness”, jokes Amanda Metskas, the director.

Campers are not told that there is no God; only that they should weigh the evidence. They learn about the scientific method. An amateur biologist invites them to gather creepy-crawlies from a nearby pond. They are told how sensitive each species is to pollution, and asked to work out from this how polluted the pond is. They find several critters that can survive only in clean water, and conclude that the pond is in good shape. The kids are encouraged to explore ethical questions, too. The more argumentative ones sit in a clearing and debate the nature of justice.

The kind of people who send their kids to Bible camp are appalled. Answers in Genesis, a Christian fundamentalist group, berates Camp Quest for drumming a “hopeless” world view into young minds. But a humanist camp is less about indoctrination than reassurance that it is all right not to be religious; that it is possible to be moral without believing in the supernatural. Nearly all the kids at Camp Quest say they find it comforting to be surrounded by others who share their lack of belief. Many attend schools where Christianity is taken for granted. Many keep quiet about their atheism. Those who don’t are sometimes taunted or told they will burn in hell.

Atheists are broadly disliked in America. Only 5% of Americans admit that they would not vote for an otherwise qualified black presidential candidate, but 53% say they would shun an atheist. That makes the godless less popular than Muslims, Mormons or gays. Granted, the proportion of Americans who say they might vote for an atheist has doubled in the past half-century, and the polls are muddied by those who do not know what an atheist is.

Only one congressman—Pete Stark of California—openly admits to non-belief. When Barack Obama was inaugurated as president, he described America inclusively, as “a nation of Christians and Muslims, Jews and Hindus, and non-believers.” But since then he has publicly invoked Jesus more frequently than George Bush junior did, according to Politico, a political newspaper. “I was surprised. I thought he’d be different,” says Valerie, a 12-year-old at Camp Quest.

The lonely 1 in 12

Although America’s atheists are not loved, they are not persecuted. Hate crimes against them are almost non-existent. In 2007 only six were reported to the FBI, and that included minor offences such as vandalism. (By way of comparison, there were 969 anti-Jewish hate crimes.) Of course, the fact that atheists are practically invisible makes them less vulnerable. A neo-Nazi can easily identify a synagogue or the Holocaust museum in Washington. But how do you spot an atheist? The guy you see walking a dog on Sunday morning could be planning to go to evensong.

Many atheists opt to remain in the closet, except perhaps with their closest friends. It is the path of least resistance. Deny the existence of God and you may be challenging your neighbours’ most deeply held beliefs. That could get you ostracised, so why risk it? Yet living in the closet has costs. Christians have their beliefs constantly reinforced by neighbours who proudly and openly share them. Atheists often wrestle with their consciences alone, even though they are perhaps 8% of the population. Christopher Hitchens, the author of an antireligious polemic in 2007, observed that half the people who came to his book-promoting speeches had thought they were the only atheists in town.

Isolation matters especially when it comes to bringing up children, a tough task at the best of times. Christian parents can call on a vast support network of churches, Sunday schools, Bible camps and incidentally religious organisations such as the Boy Scouts. Atheists have precious little to compare with this. Small wonder the kids at Camp Quest seem so cheerful.

Originally found at the Economist. By the time this is published, it may still be at this link.

1/30/09

Jim Morton, author of The Piece, "Peridromophilia** Unbound," On William James Sidis, Perhaps The Smartest Person Ever Born

About Jim Morton, author of The Piece, "Peridromophilia** Unbound," On William James Sidis, Perhaps The Smartest Person Ever Born--I found this at a site. It is the only reference I discovered. (**Love of Street Car Transfers)

-----------

Date: Wed, 30 Dec 1998 10:59:12 +0100

From: Moritz R "Moritz.R--@munich.--.de"

Subject: (exotica) Pop Void

Now that we discuss the "Funny Faces" I want to pay...

A tribute to Jim Morton:

In 1987 a magazine called "Pop Void" was published in San Francisco by Jim Morton. It was so ahead of its time that the #1 remained the only edition ever being put out (as far as I know). These were the chapters:

Those Keane Kids (about the paintings of Margret and Walter Keane)

Cars and Death (The world of Henry Gregor Felsen)

The Champagne Cult (A Tour of Lawrence Welk's Country Club Village Estates)

Ed Wood Jr. (The forgotten author)

I'm Strong But I Like Roses (A new look at Rod McKuen)

Next Year's Model (Automotive Design in the 50s)

Peridromophilia Unbound (William James Sidis)

Casa Bonita (The Disneyland of Diners)

Goofy Grape Where Are You? (The Funny Face story)

The Tonga Room (...)

Some Velvet Morning (Lee Hazelwood and the gods)

The Great American Dinner (Kraft Macaroni & Cheese dinners)

Bathtime Fun (60s Novelty Soaps)

Broiled or Fried? (Understanding the Burger King/McDonalds dichotomy)

Naked in Paradise (Social Nudism in America)

Paper Dresses (...of the 60s)

plus backpages with "Gum Report" & "Conspiracy Corner". "For the curious, who wonder what future issues of Pop Void will bring. here is a partial list of things we hope to cover:" Jim says on page 112, and what follows are about 200 subjects that cover about anything we have discussed in this list or will discuss in the future, Martin Denny, Tiki gardens, Lava lites, Disco, Muzak, the Liberace Museum, Garbage Pail Kids, Julie London, LSD, Luaus, Martini parties, Colonel

Sanders, Velvet paintings etc etc.

I guess I could spend the rest of my days on earth just working off this list in my spare time. How about Mail order pets, Silly Putty, Polka clubs, Venus Flytraps, Gumby, Suicide Knobs, Bad recipes, The Trampoline craze of 1959, Elephant jokes, Magnetic underwear, Failed soft-drinks,

Edible underwear, Bleeding Madras or White Gospel?

"Pop Void" was one of the best $9.95 investions of my life.

One question remains unanswered: Whatever happened to Jim Morton?????

-----------

I found the above appreciation at this link. As it is stored as forum chat, Blogger won't hyperlink it, so copy and paste it into the URL window.

"http://www.xmission.com/pub/lists/exotica/archive/v02.n276"

-----------

Date: Wed, 30 Dec 1998 10:59:12 +0100

From: Moritz R "Moritz.R--@munich.--.de"

Subject: (exotica) Pop Void

Now that we discuss the "Funny Faces" I want to pay...

A tribute to Jim Morton:

In 1987 a magazine called "Pop Void" was published in San Francisco by Jim Morton. It was so ahead of its time that the #1 remained the only edition ever being put out (as far as I know). These were the chapters:

plus backpages with "Gum Report" & "Conspiracy Corner". "For the curious, who wonder what future issues of Pop Void will bring. here is a partial list of things we hope to cover:" Jim says on page 112, and what follows are about 200 subjects that cover about anything we have discussed in this list or will discuss in the future, Martin Denny, Tiki gardens, Lava lites, Disco, Muzak, the Liberace Museum, Garbage Pail Kids, Julie London, LSD, Luaus, Martini parties, Colonel

Sanders, Velvet paintings etc etc.

I guess I could spend the rest of my days on earth just working off this list in my spare time. How about Mail order pets, Silly Putty, Polka clubs, Venus Flytraps, Gumby, Suicide Knobs, Bad recipes, The Trampoline craze of 1959, Elephant jokes, Magnetic underwear, Failed soft-drinks,

Edible underwear, Bleeding Madras or White Gospel?

"Pop Void" was one of the best $9.95 investions of my life.

One question remains unanswered: Whatever happened to Jim Morton?????

-----------

I found the above appreciation at this link. As it is stored as forum chat, Blogger won't hyperlink it, so copy and paste it into the URL window.

"http://www.xmission.com/pub/lists/exotica/archive/v02.n276"

Labels:

Jim Morton,

Peridromophilia,

Pop Void,

William James Sidis

6/16/04

Standing on The Corner With Omar & Satchmo

We are a puzzle, we humans. We find ourselves in the midst of life and don't know how we got here. Our parents tell us we were born. Our teachers say DNA or God or accident. None of them know and both upbringing and education are a form of propaganda which bends our minds to perpetuate the most acceptable myths. By mid life we have settled many of our questions into answers in order to concentrate on pay checks and careers and families. Still, in quiet moments we sense the old, gnawing uncertainties. We think we have settled the questions of where we came from, who we are, why we are here, and what we want, but there they are, still waiting for real answers, not doctrine, so we put them back in their place and go on with our lives until one day we die.

At our funeral, people will say he was a good man, or she was a good woman, all with the obligatory eulogy, as if words could explain the mystery of our existence, our birth and death. For myself, I would prefer a CD player and a tune by Louis Armstrong. After his trumpet licks, he would sing "Ashes to ashes, dust to dust. If whiskey don't get you, then women must." Not that the words would describe the tone of my life, but that they are sacrilegious and give the raspberry to your standard eulogy. Shocking, they would be, and I would have people scratching their heads, wondering, Was he really like that?

I come from a long line of ancestors, and will some day be one myself. As they say, I will be history. History, though, true history, is the incalculable sum of single faces shining for an instant, then gone. True history is not told by events or by nations, or by names of kings and presidents and dictators. If you want to know true history, visit the Grand Canyon. True history is Kaibab Plateau, Toroweap. It is the Colorado River cutting through geologic layers, coursing into California, all of it under the moon, which once long ago broke free of Earth, but not totally, left to orbit, and then creatures left African savannahs and became known as homo sapiens. That is history and it is also ancestry. All humanity has filed like one frightened, migratory tribe, crossing in a thin dark line across continents, through mountain passes and down valleys, kneeling to drink, then turning faces to the moon. In some distant epoch Earth itself will become a huge, faint moon, and hence a question. The question is akin to a tree falling in a forest without a person there. Will that, too, be a history, a kind of ancestry, when humanity no longer survives to know it?

That old Persian drunkard Omar Khayyam saw in grapes a temporary solution to the problems of existence, although the same problems drove his poetry . "Into this Universe,and Why, not knowing/ Nor Whence, like Water willy-nilly flowing:/ And out it, as Wind along the Waste,/ I know not Whither, willy-nilly, blowing." (Rubaiyat, XXIX) That is the irony. Even though his words posed more questions than answers, they provided him consolation, for he had created something. "And that inverted Bowl they call the sky,/ Whereunder crawling coop'd we live and die,/ Lift not your hands to It for help--for It/ As impotently moves as your or I." (LXXII) Even in his despair we find beauty.

Stand on any city street corner and you will see life's essence. Honking horns, flickering chrome, gurgling exhaust, scurrying pedestrians, fluttering pigeons, changing lights, skittering thoughts. Look again and everything is gone. All of it is solid only in our preconceptions; yet we call it real. It is Heraclitus' river that you can't step into twice. It is what we have instead of certainty. But it is beautiful, even the exhaust fumes. Beauty surrounds us and we can escape it only by closing our eyes. We are puzzles to ourselves, as is the universe to us, but in the midst of life we have more than enough to sustain us.

Take it Satch. Lead us out of here with South Rampart Street Parade.

5/7/04

Grand Canyon

In the years before its fame, the Canyon surprised the unsuspecting. They had no warning of it until they got near. There is a story of a cowboy early in the last century, riding in unfamiliar country on the Kaibab plateau. Loping along, he came to the Canyon's edge, then reined-in his horse, stopping suddenly, backing the mare away from the rim. He approached once again, cautiously, and just sat in the saddle, looking at what lay below. The sun appeared from behind a cloud and lit the immense canyons and distances in shades of color he had never seen. Finally, he patted his horse's mane and whispered to her, "Something happened here."

Below your feet lies an abyss. First the earth falls away from you by several thousand feet to reveal the Tonto Plateau. Beyond that there is another sheer drop to somewhere you can't see. You imagine that there has to be a bottom.

Looking down on the Canyon for the first time is not unlike hearing of a loved one's passing. It's hard to register, to take in. There it is in front of you but where are your bearings with it? You can't relate it to anything you've known.

It is two hundred seventy seven miles long. It could swallow fleet upon fleet of trucks or battleships into its depths. It existed long before apes began walking upright on African plains and savannahs. With such immensity, you would think it had always been there, but the Canyon and its river were slow realities. The soil of the rims came from somewhere else by wind and water. The earth was covered by shallow coastal waters with active volcanoes. For millions of years sediments and lava accumulated thousands of feet thick. About 1.7 billion years ago tremendous deep, internal forces caused the layers to buckle. The earth rose up to meet a coursing stream, imperceptibly and relentlessly and the Canyon slowly was born. Mountains five or six miles high arose and were worn down long before any human saw them.

Vishnu, the Hindu god of creation had played his terrible force. Igneous rock was transformed from heat and pressure and out of ordinary soil. Geologists call it Vishnu schist.

Wind and water then began to carry off the mountains grain by grain over long centuries and millennia. The Colorado runs swift and fierce, tumbling through the gorges and indifferent to the unhappy animal who falls into it, swirling the creature along and plunging him through rapids to his death. The strata on the cliffsides eroded and revealed millions of years of life, trilobites, reptiles, dinosaurs, mammals, all layered over as the earth of centuries covered them inch by inch, clod by clod, until very near the top human beings come upon the geologic scene, dressed in a little brief authority.

The geological formations can be classified. The periods are Pre-Cambrian, Devonian-Cambrian, Paleozoic with Mississippian and Pennsylvanian, and the Permian. The strata are Dark Gray, Vishnu schist, Tapeats Sandstone, Grand Canyon super group, Bright Angel Shale, Muav Limestone, Temple Butte Limestone, Redwall Limestone, Supai Formation, Hermit Shale, Coconino Sandstone, Toroweap Limestone, Kaibab Limestone. The count of periods and sub-periods is six. The count of strata is thirteen.

Having identified these categories and counted them, I have said nothing. Should I say 800 million years of advancing and regressing oceans, of marshes and mountains, I still have said nothing. If I stand on the rim and look in silence a glimmer of understanding comes to me.

In 1540 the Spaniard Cardenas was the first European to cast eyes on the Canyon. He was a member of Coronado's expedition and had been dispatched to scout the region. For his queen he was seeking gold in the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola. He was in no mood to enjoy the scenery or to look up in awe at the Canyon walls. He did not find gold nor get to the Canyon bottom. After five or six days trying to find his way down he turned back in defeat. He had been led on in the hope that there would be a place, an end, where his difficulties would be over.

In 1857 Lieutenant Joseph C. Ives conducted an extensive reconnaissance of its western end for the US Government. The Arizona Territory was desolate and uninhabited and his report was confident--Ours has been the first and will doubtless be the last party of whites to visit this profitless locality. It seems intended by nature that the Colorado River, along the greater portion of its lonely and majestic way, shall be forever unvisited and undisturbed. He would never know that a little over a hundred years later a thousand visitors a day would see the Canyon.

In 1869 the next white man came from five hundred miles away in Green River, Wyoming, up the boulder-strewn rapids in twenty foot wooden boats. He was Major John Wesley Powell, a rugged man with one arm lost in the Civil War, a man with a proper Methodist name bestowed by his minister father. Before he started his journey the best maps showed blank space where he explored. Had they been charted in Medieval times they would have carried the warning, Here Be Dragons.

For months back East, rumor was that the Powell party had been lost. The Major and his mountain men knew nothing of this rumor and felt adventurous rather than lost and so pressed forward. Some of the rapids were so turbulent and treacherous that they planned to portage their boats whenever safety indicated. A few of the men would never have gone on had they known that ahead canyon walls were so sheer at water edge that there was no choice but to shoot the rapids.

In his journal Powell wrote The walls now are more than a mile in height . . . A thousand feet of this is up through granite crags, then steep slopes and perpendicular cliffs rise, one above another, to the summit. Earlier he had written that the great river shrinks into insignificance, as it dashes its angry waves against the walls and cliffs, that rise to the world above . . . We have an unknown distance yet to run; an unknown river yet to explore. What falls there are, we know not; what rocks beset the channel we know not; what walls rise above the river, we know not.

When I first looked upon the Grand Canyon I held a camera to my eye and couldn't get the shot I wanted. The lens just couldn't encompass all that was there, couldn't bring it any nearer.

Eventually it occurred to me that the only way to get close to the Canyon was to establish a relationship with it, and that took time. After a lifetime, I would be a little closer to it, but not much.

We are such things as dreams are made upon, and our little lives are rounded with a sleep, said Prospero in Shakespeare's The Tempest. The words returned to me in the Canyon. Wherever I looked I saw the dreaming centuries. The hikers seemed sleepwalkers marvelling at the brightness of the dreamscape. We were all passing through, light moving on shadow, mind upon silence, comforted by the noise that the wind and the river offered back to us to assure ourselves that we were real. Real in the solid, abiding sense. Deep down, on the other side of the Colorado, I came upon rocks with words scratched in them, B. Andrews was here, 6/9/1963. I looked at the muddy, fast current, and thought about the hike back to the rim, unaware that one day I would write this blog article that would not last as long as the man's scratchings.

5/3/04

Beautiful Sardines

The Study in Aesthetics

The very small children in patched clothing,

Being smitten with an unusual wisdom,

Stopped in their play as she passed them

And cried up from their cobbles:

Guarda! Ahi, guarda! ch’e b’ea!

But three years after this

I heard the young Dante, whose last name I do not know—

For there are, in Sirmione, twenty-eight young Dantes and thirty-four Catulli;

And there had been a great catch of sardines,

And his elders

Were packing them in the great wooden boxes

For the market in Brescia, and he

Leapt about, snatching at the bright fish

And getting in both of their ways;

And in vain they commanded him to sta fermo!

And when they would not let him arrange

The fish in the boxes

He stroked those which were already arranged,

Murmuring for his own satisfaction

This identical phrase:

Ch’e b’ea.

And at this I was mildly abashed.

I sit on the front porch, taking in the sky, feeling the breeze on my cheek, watching birds flit from tree to tree. A cloud drifts overhead, and its shape is radiant of the morning sun. An ant crawls over my shoe, then down its other side, continuing toward a crack in the concrete. I know if I don't move my shoe another ant will soon follow the spore, up over my shoe, down the other side, into the crack. At the moment, I don't care. With the sun in its ascendancy, the ant on my shoe, I am beyond even the Cistine Chapel in the Vatican. Adam's finger reaches across the dome for God's miraculous touch. It is all there, in that sky, the breeze, the birds, the ants, the sun. I am Michelangelo and this is the moment of Creation. I am both Adam's finger and God's touch. This is beauty, and it is all.

Somewhere in The Hero With A Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell said that people don't search for meaning. Instead, they seek to live in such breadth and depth that life itself becomes the meaning. In Zen and The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert Pirsig says that quality transforms, and that whatever we think we seek, we are really after quality. Both Campbell and Pirsig have in mind a beauty that can't be named, and it is this beauty that yields truth, a truth worth living for. It is an experience, not words, images, or numbers.

John Keats said that truth is beauty, beauty, truth. Paul Dirac would have agreed with him, although he had his equations in mind. "It is more important," he said, "to have beauty in one's equations than to have them fit the experiment." He meant that "if one is working from the point of view of getting beauty into one's equations, and if one has a really sound insight, one is on a sure line of progress." When asked how he recognized beauty in his math, Dirac replied that he felt it. It couldn't be explained. Nobody can explain it. He added that it's like Beethoven. If somebody doesn't appreciate the beauty of, say, the Ninth Symphony, then nothing can be done for him. Dirac stated that Einstein had this same point of view.

With beautiful sardines is where it all stops, of course. You can't get any further than that. Oh, don't get me wrong. The aesthetic sense can take you into theories, equations, poems, symphonies, canvases, and fine thoughts, but you are moving away from it. Once you are in that moment, you have all the truth you will ever have. Yes, a Buddha can expand its opening, but that's it. Everything else is an attempt to explain it. Quantum theory spins itself out of an exquisite aesthetics, as does good poetry, but they are lain over that which we ultimately cannot describe, which is what Persig finally says with his qualia.

It is the mystery that mind tries to explain, but which will always remain as a dimension of the universe unavailable to our understanding. One of the Upanishads, says "When you see a sunset or a mountain and you pause to exclaim, 'Ah,' then you are participating in divinity."

And at these moments we are at least mildly abashed.

4/20/04

Home______An Infinity of Mirrors: From A Book In Progress

Suppose that time is an infinity of mirrors, in front and in the rear, receding forever into the distance. As you look behind they take you deeper into them and backward. You are carried past your day of birth, past your parents, past your grandparents to the beginning of something.

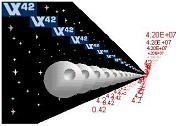

Suppose a world in which all possible consequences play themselves out. Chance and deviation are infinite. We live on and on as we exhaust one variant life after another without ever running out of them.

In such a universe this book would be written both the same and differently by me. And it would never be written at all. If I write all life scenarios the early versions fill the New York City public libraries, and soon a stack of books stretches out into the universe.

Suppose that one scenario would be lived thus: Chapter one, Rolly stays in Ohio to inherit his uncle's farm. Chapter two, his wife dies in childbirth, leaving him with one girl and two boys, all young. Chapter three, he meets a girl half his age in Springfield, and they get married. Etc.

In a world where all potentials are realized, one is that Will would never return to California from Ohio because his parents never left Xenia.

Suppose a day with Valentine on a barge when river pirates at Die Maus, an island in the Rhein near Ruedesheim, stop the boat to demand toll money from him and his fellow passengers. Suppose that he is left without enough money to get to Amsterdam and hence America and he turns back to Switzerland.

Suppose then that Will was not born because Valentine never made it to the New World. If he was not born he never met his wife nor did they have their daughter. This is a supposition I can't get rid of no matter how I think about time. It remains as potential when I consider it.

In Zen there is a puzzle, What was your face before your parents were born? An omniscient being could crack it without having to meditate, but then, God doesn't need koans.

In another version of the cosmos, time never created earth. The fiery gasses that spun off from the sun and chilled into seas did not do so after all. Or they did and life never occurred. They orbited too far from the sun or too close and temperatures could not support organisms.

Earth both existed and it never existed. Human beings lived and never did. Of course I am not here writing this and here I am. You the reader never read it and here you are.

In a world where all is potential there is paradox. When we see our face before our parents were born it disappears. As a push out of one moment into the next, time stops. It becomes effortless, a flow, or nonexistent.

In this version of time, death becomes unimportant because we will one day live and we will never live. It follows, then, that we will die and we will never die. We will live out countless lives and we will live out none of them.

Home

4/16/04

Death and The Sense of Self

Nunc lento sonitu dicunt, morieris. (Now this bell tolling softly for another, says to me, Thou must die.) John Donne Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, Meditation XVII

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were. Any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee." (John Donne, Meditation XVII, from Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions, 1624)

Three hundred years lie between Donne's No man is an island and Einstein's remark that a human being is part of a whole (discussed below), and each involves a contemplation of death as a type of illusion.

Early in his life, Albert Einstein became aware of the illusions begotten by common sense. As a boy, he imagined himself riding a light beam and speculated on how things would appear as he approached the speed of light. Understanding the new shapes they would assume, he concluded that the universe is a strange place indeed, providing little to verify common explanations of it. He grew up to demonstrate this strangeness to the entire world. which proclaimed him a genius for theories it could not understand. Einstein set aside common sense to usher in a perspective that, to the cab driver and the politician, offered nothing but nuclear bombs. To poets, he brought forth Yeats' question, What rough beast, its hour come round at last, slouches toward Bethlehem to be born? To Einstein himself, nothing comforted in the world he had opened for physicists such as Neils Bohr, who told him that all was random, mere chance. No, Einstein replied to Bohr, God does not play dice with the universe. This, he could not accept even to his death bed.

He eventually allowed Bohr's Complementarity Principle as the most rational explanation for quantum events, which is to say the wave-particle duality, persisting to this day as the central puzzle of quantum physics. (Richard Feynman said that if you aren't troubled by it, you don't understand it.) He also came to accept that he wasn't who he thought he was. Nobody is. We are all something other than what we think we are. We are, so to say, not our selves.

Wave-particle duality indicated the failure of a classically materialist explanation of the universe. Later, with experiments such as John Bell's and Alain Aspect's,* the nature of things appeared as non-local, a remarkably weird feature of the universe, but which photons fired 40 meters apart consistently suggested. Matter itself seemed not specific to a point, but instead participated in a different kind of space, one inhabited by a consciousness belonging to nobody in particular and everything in general. * (See them in Non-Local Reality, 10 November 2003.)

Einstein had thought about consciousness when faced with Bohr's Complementarity and, after deliberating on it, he again concluded with an idea that the cab driver and politician would take as bizarre.

If the universe cannot be described by material points in space, by discreteness, said Einstein, then, as a collection of matter, the separate human self is an illusion:

"A human being is a part of the whole, called by us the 'universe,' a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separate from the rest--a kind of optical illusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from the prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty. Nobody is able to achieve this completely, but the striving for such achievement is in itself a part of the liberation and foundation for inner security."

By this remark Einstein stepped out of classically scientific considerations into the spiritual life which, in a sense, had formed his basic temperament. It had helped spur Einstein as a boy when he imagined himself traveling on a beam of light, for his universe was one with a grand design that allowed human understanding or mystery wherever mind probed. Nor was he far from poetry in his regard for beauty. "Death is the mother of beauty," said poet Wallace Stevens. In its contemplation we see our limits as individuals, as he did.

Death is the final liberator, and from its freedom none do escape. It is the mother of compassion, and as Wallace Stevens said in another context, "Hence, from it all things must follow." The liberation itself lies in Einstein's words if we can but fathom their profound implication. There's nobody at home. Nobody is telling the story. The story tells itself, with the story teller woven into the plot.

People find this unacceptable. Death, they say, is the obverse of life, and spurs us into creative energy. We want to leave something behind, to make a mark, something that lasts, so to establish ego beyond the grave. We would not die without having lived, our lives understood as a self making coherence of the world.

Einstein may not have fully grasped his own meanings, but at bottom his implications are that ego cannot die because it was never born. As he puts the situation, ego is an optical illusion of consciousness. People would gladly accept non-death if they could but understand it, deeply, fully, after they have died unto their egos. What died was fiction.

This is not so much theory, and is available to science, a different kind, one that silently examines consciousness. Its practitioners have been many, and one was Sri Ramana Maharshi, who wrote to Mercedes De Acosta in response to her book, Here Lies The Heart. Without ego, the world is. Of the egoless state, he said, "The Gnani (the Enlightened) continually enjoys uninterrupted, transcendental experience, keeping his inner attention always on the Source, in spite of the apparent existence of the ego, which the ignorant imagine to be real. This apparent ego is harmless; it is like the skeleton of a burnt rope--though it has form, it is of no use to tie anything with." (See Mercedes de Acosta and Ramana Maharshi, 24 January 2004 at the Occasionals site.)

Ramana Maharshi also said, " Your glory lies where you cease to exist." This is not a uniquely Hindu vantage, and can be found in Christianity. St Gregory said, " No one gets so much of God as the man who is completely dead." A Medieval German, Meister Eckhart advised, " The Kingdom of God is for none but the thoroughly dead" and William Blake told us that " We are in a world of generation and death, and this world we must cast off." Each of them had arrived at the same understanding although their paths were different.

"We are such things as dreams are made on," said Shakespeare's Prospero, "and our little lives are rounded with a sleep." Of that sleep, John Donne's contemporary, Sir Thomas Browne, remarked, " Our longest sun sets at right descensions, and makes but winter arches, and therefore it cannot be long before we lie down in darkness, and have our light in ashes." * He urges us to make much of time.

Zen Buddhism teaches that form is emptiness, emptiness, form, and all participates in the continual change that is life and death. Ego vanishes and reappears, as do thoughts and lives. Shadows lengthen inside Buddhist zendos when disciples chant the Evening Gatha:

Life and death are of supreme importance.

Time swiftly passes and opportunity is lost.

Each of us should strive to awaken.

Awaken!

Take heed . . . Do not squander your life.

Their voices trail off with the last syllable, carrying it into the silence, from which new sounds will emerge. A baby cries, spanked into life in the delivery room while in another part of the hospital an old woman's eyes shut for the last time. Albert Einstein, John Donne, all of them appeared and vanished, just as you will leave this page and these words will fall from your mind, our brief contact over.

* Hydriotaphia, or Urn Burial, 1658

3/25/04

Home______Deconstruction As Fashionable Nonsense

As a child, I could hear fog horns on San Francisco Bay during the night. Beeee-oohhhh, they would groan in deep bass, then repeat themselves, beeee-oohhhh, until the sky cleared some time next morning. Fog was my friend, then. It made me feel warm and cozy in bed and hopeful of light drizzle on the walk to school next day. Even today I enjoy misty weather and dark pavement glistening with moisture under street lights. But, of fog, there are two kinds of atmospherics, and I have come to like the other type less as I grow older. It has to do with intellectual fog.

Recently I opened a book titled Entropy: A New World View, by Jeremy Rifikin, and read this as an application of the Second Law of Thermodynamics: "Every day we awake to a world that appears more confused and disordered than the one we left the night before. Nothing seems to work anymore. Our lives are bound up in constant repair. We are forever mending and patching. Our leaders are forever lamenting and apologizing. Every time we think we've found a way ouf of a crisis, something backfires. The powers that be continue to address the problems at hand with solutions that create even greater problems than the ones they were meant to solve."

Now, that sounds quite powerful, that prose--it has a roll, and a tone, but it means nothing. If Rifkin said to the reader that he is taking license with the scientific concept, entropy, then I would string along with him. But he is quite serious in applying the Second Law where it does not belong. He says this about that: "The entropy law destroys the notion of history as progress. The entropy law destroys the notion that science and technology create a more ordered world."